Signs of Life (Instagram)

in which i document my permaculture diploma and ferment change in the kitchen… and beyond.

Some of you might be aware that Tim and I are planning a move (back) to Western Australia over the next couple of years in order to have a stronger connection to the earth and our family. I’ve been living in Europe for more than a decade and Tim has spent over half his life in Linz and we want to maintain our connections here, but it is time to get back to our roots. Our niece and nephew are growing up a town over from our planned destination and it will be amazing to be closer to our parents and siblings even if Australian ideas of “close” still mean half a day’s travel or more.

It will also be a chance for us to keep our fingers dirty more of the time and to build a flourishing home and garden system that is resilient against climate and socio-political changes. While we are both involved in making and growing things on a regular basis at home and within community spaces, the window sills of our apartment only offer so much growing area that is truly ours.

In particular, there are some permaculture-related goals that we want to put in play but which don’t work in our current location. While we have a worm farm that makes use of some of our food scraps and use renewable energy (go Austria!), we are still heavily dependent on municipal systems for the rest of our organic waste, on (regional) supply chains for food and would be very vulnerable if the electricity grid failed. Having more influence on our waste-management and energy systems and providing animal protein for us and our family in an ethical and scale appropriate way are responsibilities we’d like to take on. But generally, I’ve been considering the idea of a productive and resilient peri-urban block as just a hypothetical idea for the last months

So it is pretty funny, and at the same time an important step when one of those dreams became a fixed puzzle piece. One night last week we followed up on a Kickstarter project and spontaneously invested in a small bio gas system so that we can turn our future kitchen waste into fuel for cooking. I’ve been intrigued by anaerobic digestion for years and my interest grew when a friend I met on a permaculture course described how she fried her breakfast eggs using biogas. It must have been that vision and the crowdfunding head rush that prompted me to then back another Kickstarter for information about raising quails and plans to build the world’s best quail tractor system.

Apparently the biogas breakfast idea connected with another fond memory of being served nettle soup with a tiny fried quail egg on top. So there you have it, we are slowly turning dreams into at least the puzzle pieces of the life we will have in the future.

Of course, every action sets off a new change of questions and decisions – when one has multiple options beyond the municipal organic waste bin, how does one prioritise where their waste goes? What goes to the worms or the quails and what goes straight to the bio-gas digester? How best to site and shield a biogas unit for year-round gas production (output drops in the cooler months) and even though it won’t explode, ensure that it is safely managed in a high-fire risk region?

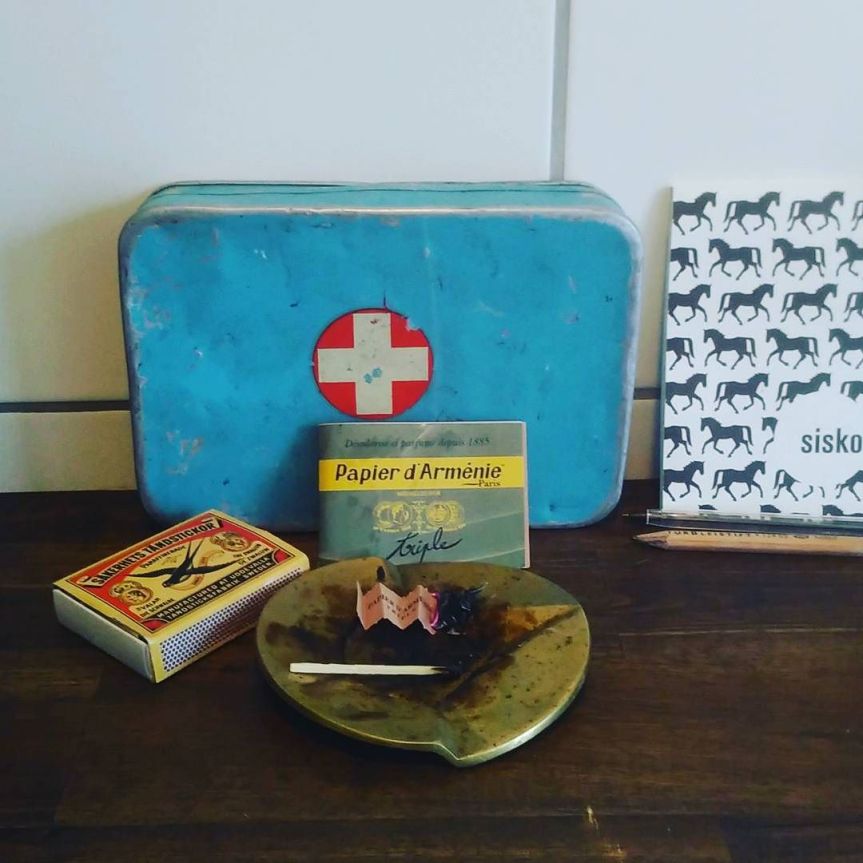

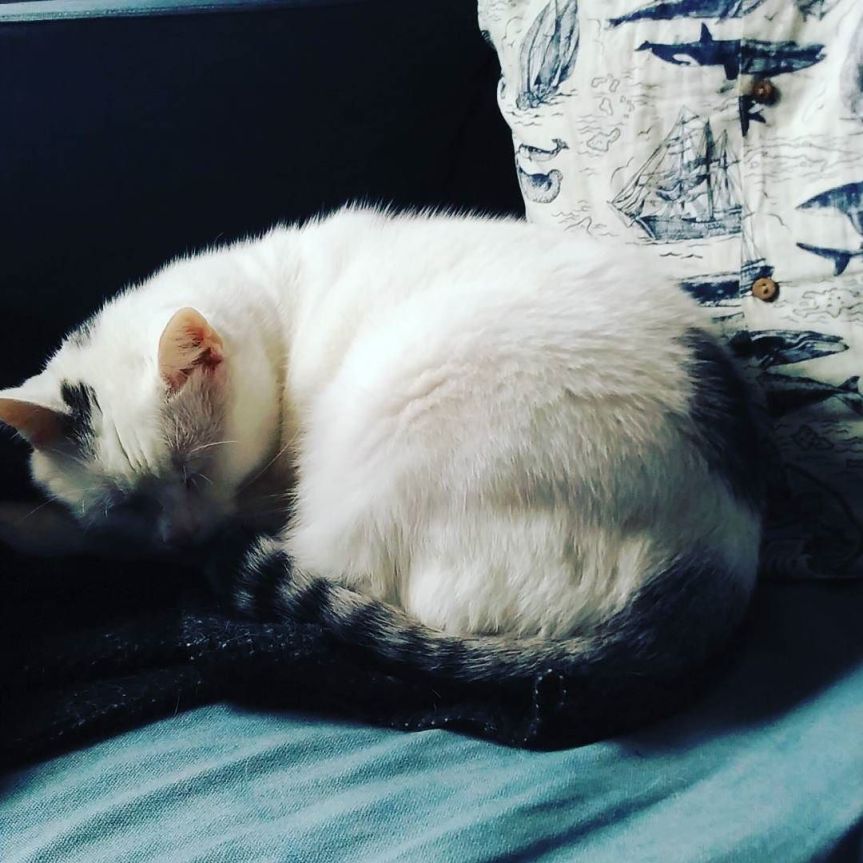

And maybe more importantly, there is the question of how best to remain in the now when such exciting future plans become more real. Though that can simply be answered through caring for my current home system including worms and Seagull the Cat, who will have to stay here in Austria.

Apparently this blunzn is made to a Lower Austrian recipe, but rest assured Aussie friends we will try to source / replicate this should any of you ever want to give it a try.

#blunzn #ethicalmeating #nosetotail #iron via Instagram http://ift.tt/2j075Ut

The Maths Captain and I finally put our electric motor to the test and took The Runcible Spoon, our long-refashioned sailboat over three hours and 12 kilometres up the Danube to Ottensheim for Ottensheimer Cremeschnitte (not just any Konditorei cream slice, but one with a special dash of redcurrant jelly). E-motoring back down to Linz with the current took just an hour and ten minutes but even so, such a journey is a little tedious when you’re not sailing but especially when you discover the cooking gas is empty and you can’t cook an adventurous cup of tea in the tiny sailboat “galley” on the floorboards. (Boat tea is the best-tasting tea ever).

The journey back was made far a little more exciting as I had collected fallen twigs covered with lichen at the mouth of the Rodl river where we anchored. On the return journey I used The Maths Captain’s knife to scrape off the lichen into a little beeswax cloth, ready to dry and process as a dye for wool. A lovely acquaintance of mine who teaches nature connection cautions her students to only gather and forage what nature is giving freely. Normally, I’d leave lichen on trees and rocks as that is where it is doing lichen services like photosynthesising, rock decomposition, soil formation and looking lovely as well as being a bio-indicator, but a recent storm had shaken these dead twigs and small branches off to the banks of the Danube and Rodl and were about to be washed away into a very big and commercial river. A gift indeed.

::::

Even though I somehow knew that lichen could be used as a plant dye, I didn’t exactly know how the colour should be extracted and it turns out that C+ lichens (I made a test with bleach) can produce a pink-violet colour when fermented over months with ammonia, or historically, stale urine.

So here we are in the modern world where urine, a freely surrendered resource, along with commercial fertiliser runoff ends up polluting waterways as ammonia naturally forms. Permaculture co-founder Bill Mollison describes a pollutant as any output of a system not being used productively by other parts of the system. Permaculturists and other organic gardeners are onto this and often use fresh, diluted urine as a natural way to add nitrogen to the soil, combined with carbon rich matter in compost heaps. Of course, if using a composting toilet makes sense, a urine diverting toilet seat makes it even easier to gather the flow of urine’s nutrients.

::::

Thinking about processing my 20g of dried lichen with my own, stale urine, and wondering what pink or violet accent colour I can incorporate into a knitting project is obviously just a starting point for a number of distractions including other natural dyestuffs (indigo! black beans! avocado pits!), the ethics of foraging and wild food and colourstuffs and whether I should ferment the carrots sitting in the fridge. Often though, these distractions contribute to a line of thinking about how dependent our lives are on globalised, late-stage capitalism and fossil-fuel dependent industry

Even when we claim to be self-reliant, back to nature or simplifying our purchasing patterns by say, dying and making our own clothes, cleaning with vinegar and baking soda, minimising packaging, or “frugally” cleaning the oven with just ammonia rather than an over-priced commercial oven cleaning product we remain entangled. We still need to get those basic ingredients from somewhere, even if they come in bulk or are traded in a non-monetary economy – they are still dependent on the industrialised system. What on earth will we do if this brittle system breaks? It’s enough to make me hoard baking soda and consider cleaning the oven with stale piss – though of course, in that potential scenario there would be no electrical grid to supply my apartment kitchen with power, so I wouldn’t be able to use the oven, clean or dirty. I think I would happily keep my standards low – the oven hasn’t been properly cleaned since I started my Masters degree and will probably stay that way for a few months more.

The box of pinecones I have gathered for the storm kettle is nothing in the big scheme of energy vulnerability and possible futures both good and bad. It is one thing to make a pot of herbal tea or have an off-grid home, but how would roads be repaired, materials for infrastructure quarried and foundations for bridges dug in a low-energy future? And I think here not only of a low-energy future in the framing of peak-oil, but also in terms of low-energy when energy distribution fails, demand becomes too high or the global financial system reveals its inherent fragility.

I can use pinecones to heat my tea, but even electrically powered digging machinery requires vast forms of electricity from a stable system. Without energy to power industrial tools, we go back to manual, human labour, without a functioning economic system that exchanges value for labour, our societies could easily return to a large-scale slavery model. It is tempting to think that forced labour hasn’t existed since the abolition of slavery and serfdom. However, slavery and indentured labour is still present in the modern world and touches us indirectly through the goods we buy and services we make use of.

This Twitter-story by Samuel Sinyangwe on racism, incarceration and labor exploitation in Louisiana, USA reminded me of the yet another way that slavery is present in modern life, though one that is far more mandated by the state than drug and food growing, the sex-industry or shellfish-production. William Gibson is reputed to have said that the “future is already here, it is just unevenly distributed” and with that in mind I began to chase down leads on the potential return to slavery in a peak-oil, low energy world, including a call to move away from “energy slavery” to participatory democracy and appropriate technology from Ivan Illich.

I think that where my thoughts have been going with this is that 20g of lichen, my own urine and pinecones could all be considered as “gifted” resources along with the gifted labour of friends have helped us to restore the boat, whereas exploitative use of nature and humans can only be thought of as extraction and theft. But at what point does foraging of nature’s gifts or cooperative and volunteered labour practices step into misuse?

I am reminded of the permaculture ethics and how directly they relate to Principle 5 to Use and Value Renewable Products and Services of co-founder David Holmgren’s interpretation of permaculture principles. In Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability Holmgren discusses valuing ecosystem services, wild products, water and working animals but doesn’t directly include valuing the labour of human inputs into a system. The People Care ethic and _efficient_ design is inherent to permacultural practice, so maybe “avoiding the need for exploitative labour practices and slavery” doesn’t need to be said or considered in the immediate systems such as homesteads we have the opportunity to design, we should be careful though. Like so many things though this reminds me of why we need ethics-based approaches like permaculture at a higher and more widespread model so that we design societal culture futures to avoid widespread slavery too.

It is the festive season and there has been a lot of parties, drinking and catching up on years passed and the tricky question “What are you working on?” After a drink or two I may end up working through the litany of issues that occupy my thoughts: performance and security of energy provision infrastructure against climate threats, unsustainable building materials and design, social inequality, vulnerability, isolation and an aging population, changed social practices and expectations of warmth and coolth, social norms and air conditioning, existing environmental threats and a rapidly changing climate and governments, industry and populations not sure how or what to respond to. If I am not yet in my cups I say “Heat waves. I’m working with people to develop heatwave plans.”

Having grown up in an Australian Mediterranean climate and now living in continental temperate Europe my cultural experiences and understanding of Austrian climate and its changes are somewhat restricted. That said, the changes in snowfall that have been apparent over the 7 years I have passed in Austria are visible and culturally present. As an Austrian bank teller confided after I queried whether my bank was divesting from fossil fuels, “My children have never built a snowman.” Upper Austrian adaptation plans identify threats to hydroelectric power generation, propose establishing wine regions in the Muhlviertel and also predict radically changed winters and the loss of ski tourism. I tried snowboarding once, but cynically have avoided over-investing in ski culture and equipment.

Returning to my hometown to celebrate Christmas Day with my family for the first time in at years the cultural memories of climate and its new incarnations are stronger. On the 25th the top temperature broke records, reaching 41°C. My memories are that it was often cool at this time of year, in the 20s on the 25th. The heat that laid us out three days ago is something I always associated as happening in January and February when heatwaves traditionally hit. In central Australia rainfall and flooding led to evacuations. I was reminded of Cyclone Tracy which devastated Darwin on Christmas Eve in 1974.

There has always been extreme weather, but it is changing its patterns.

Two days later and the weather has become tropical: clothing and paper feels moist to the touch. Last night a wonderfully exciting, yet destructive storm came through the state. My partner and I have been sleeping in my mother and stepfather’s camper trailer and the wind and rain felt deliciously intimate to our tiny protected bubble.

Across the city trees are down and homes and industry are without power. Luckily my Mum’s place still has power, is undamaged and is just very soggy. There are fewer young avocados on the trees though, but the larger fruit has held firm.

They are big thoughts which support my research yet can easily distract from the around the more practical and urgent thoughts of _dissertation_ preparedness. Review the proposal, put out a call for participants, make some heatwave plans and analyse the conversations and write it up by June 31st. Then I can think about changing the world.