I love so many aspects of permaculture: the delicious food produced by permaculture gardeners, the sense of global and local community it fosters, the sustainable changes it has supported me to make in my life and the beauty in the nature it helps me see. At a more pragmatic level I also know that permaculture gives individuals, households and communities the tools, attitudes and skills we need to design abundant, inclusive and resilient futures.

This mix of sustainability and resilience is one of the delightfully simple, yet complex aspects of permaculture. A well-designed and managed permaculture system will be resource efficient, productive and may well sequester greenhouse gases, but it will also be a resilient system better able to deal with the inevitable effects of climate change such as natural disasters like floods or wildfire.

The potential for disasters happen when systems can not handle extremes or cumulative stress. One week of limited spending may be a challenge, but a medical bill on top of long-term debt and structural poverty may force a family into homelessness. Water is essential for life, but the extremes of either drought or flood-causing torrential rain can cause havoc in both natural and human systems.

Designing land, the built environment, lifestyles, livelihoods and organisations to deal with extremes as well as everyday conditions is essential for resilience. Resilience is the ability of a system to handle change. There are many ways in which permaculture design and practice supports resilience. In order for designers to design for resilience, they first need to understand what extremes are most likely to have an impact on a site. This is why careful observation and sector analysis is so important for a successful project.

In this video from the Permaculture Women’s Guild Permaculture Design Course I get really excited about sector analysis and visualised data like wind roses. Then again, I am really excited about permaculture and regenerative design in general.

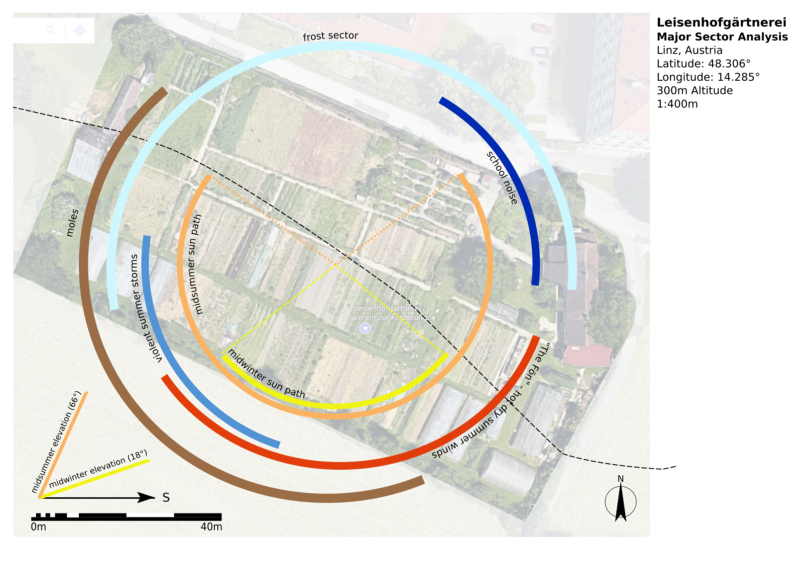

Sector analysis is a critical tool for visually representing observations about identifying how a site may be affected by the “sectors” or the external forces and elements that move through or otherwise influence a project. The sectors recorded can be related to effects on the site caused by climate, ecology, geology, topography and society. For example sun paths, wind and rain patterns, invasive plants, wildlife, pollution, neighbours, areas of high fire threat, views and noise could all be recorded on a sector analysis map.

Sectors are often represented as labelled wedges, arcs or arrows representing the origin and direction of the element. However, rocky areas, contaminated soil, boggy land, or areas of flood risk are better represented as location specific patches over a base map. Some uncontrollable issues such as geological instability or limiting factors such as legal restrictions are harder to represent visually and are best recorded in writing.

In the Permaculture Women’s Guild Permaculture Design Course (PWGPDC) my colleague Jennifer English Morgan introduced the idea of Designer’s Mind. One aspect of developing Designer’s Mind is about making observations free of bias. The forces recorded on a sector analysis are neutral and can be both beneficial or harmful. For example knowing that dry summer winds come from the east of a site helps identify the best place to locate a laundry line or to hang produce for drying. At the same time that drying wind will quickly evaporate water from soil as well as dams or ponds. This information guides the placement of windbreak plantings or hedges on the eastern side to moderate the impact of the wind and reduce evaporation.

Used together with permaculture design tools such as zone analysis, sector analysis helps guide the placement of components so that they make best use of, or mitigate the risks of that sector. Sector analysis influences which zones are placed where, but at the same time, zones influence the strategies used to respond to external forces. In outer zones such as 3 or 4, lower cost, less energy demanding solutions such as windbreak plantings are used to slow the wind. Closer to the home more intensive solutions such as walls or use of gray water might be used to protect water-demanding plants, animals and people from a drying wind.

Permaculture designers make a sector analysis for every design project whether it is a farm, balcony garden or community project. Within larger designs, major subsystems such as high intensity vegetable beds may also benefit from their own sector analysis that includes smaller scale micro-climate influences like the impact of trees casting shade.

Working on sector analysis is a great way to review and incorporate the ideas from Permaculture Design Course modules on climate, ecology, water, earthworks, soil and passive solar building design. Knowing how and why to make a sector analysis is a first step in designing mitigation approaches for the major extremes whether they be fire, flood, drought or legal challenges.

You can learn more about sector analysis and other aspects of permaculture design and practice in the Permaculture Women’s Guild Permaculture Design Course (PWGPDC). Along with my colleagues we’ve put together an online learning experience which includes advanced modules on social and emotional permaculture as well as core land-based permaculture content.

In the PWGPDC I present an in-depth module on Designing for Resilience: Chaos and Catastrophe. I consider the social and structural conditions that make people more vulnerable to disaster as well as the design approaches we can use to make our sites safer. My final Masters project explored how natural hazards are dealt with by permaculture designers and teachers and my results showed that “designing for catastrophe” is currently focused on the physical aspects of disasters rather than the people care aspects that increase coping capacity.